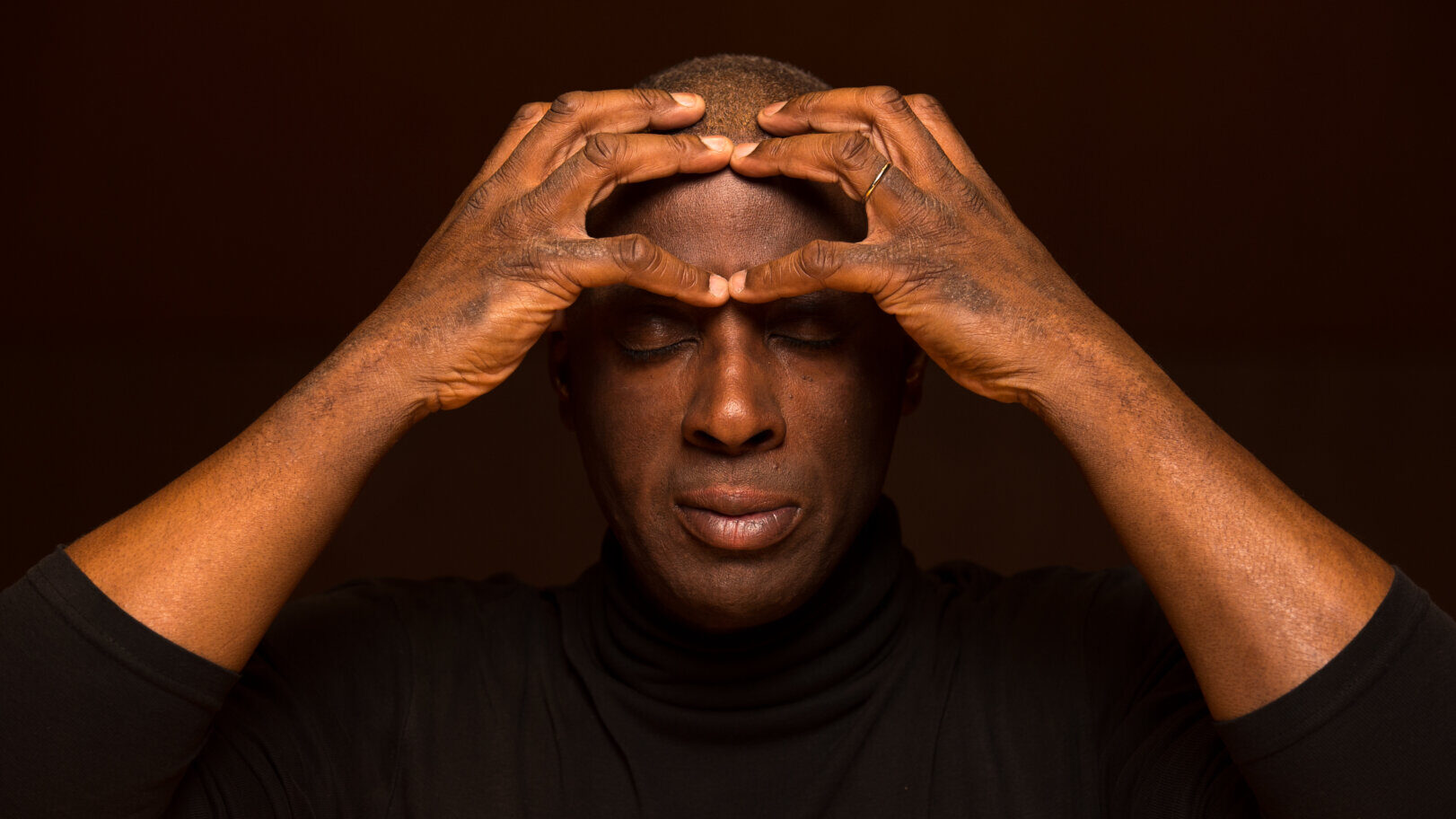

Hearing Wayne Marshall perform on Müpa Budapest’s great organ on 8 February will completely rearrange your thinking about what the ‘King of Instruments’ is capable of. A master of improvisation, this British organist frames his programs with it. His mixed program of the old and the new will be bordered by his own free improv, taking his musical cues from several centuries’ worth of great masters.

Marshall, who also doubles as a conductor, took the podium of the WDR Funkhauser Orchestra in Cologne from 2014-2020, and serves as Principal Guest conductor of the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi. This month he makes his conducting debut with the Munich Philharmonic. As an artist whose distinctive musical purview reflects a life-long, multi-genre education and experience in the musical sphere, he was honored with an OBE (Order of the British Empire) from Her Majesty The Queen’s New Year’s Honors list in 2021.

He has played famous organs in major concert halls and churches all over the world, and will be making his Budapest organ debut in Müpa with a program of music by the great romantic French masters Widor and Dupré, newer works by George Baker and Andrew Ager, and will leave the Béla Bartók National Concert Hall’s walls ringing with his hallmark symphonic improvisations.

– Are you excited about playing Müpa’s new organ?

– I can’t wait to visit this new concert hall because I haven’t seen it yet, as well as its organ which I’m really looking forward to playing. And of course, I’m happy that this concert is actually going ahead, because this is the second try – it was originally scheduled during the time when the pandemic cancelled everything.

– What’s your basic approach to planning your programs?

– The organ is basically an orchestral instrument. It’s got lots of possibilities. I try to select repertoire that is really going to show off the organ. I want the audience to hear what the organ can do. It’s always a compliment when people come up to me and say: “Oh, I didn’t know the organ could do that!”

It’s all in the choice of repertoire, and I like to player fewer, longer, pieces in a program, rather than a long list of shorter pieces, which I think is very boring. The one thing that I always do in my recitals is improvise – no question – I improvise at the beginning and at the end. That gives me a chance to explore the organ a bit and introduce the instrument to the audience so they hear it in a different way, rather than to launch immediately into repertoire. This is very, very important for me: I need space in the concert to be creative. For the written repertoire, my creativity comes with how I register [electronic or mechanical pre-set of selected sound sources within the organ] the piece for that particular instrument. As a solo artist, I need my own outlet to do what I want to do. That’s why I always conclude every concert with an improvisation.

– Which is your favorite era of organ compositions?

– French repertoire is my favorite. The language of composers like Widor, Vierne, Dupré, et al., really speaks to me because their music was written at the time when organs, at the beginning of the 1900s, were in the midst of a huge transformation. The idea of getting away from the Baroque-sounding organs was a big departure. They became much more orchestral in style and in construction. The new repertoire that was then being written, of course, reflects that. That’s why it speaks to me in a way that Baroque repertoire doesn’t; Baroque, of course, speaks to me, but in not in the same way. My emphasis was always on this kind of virtuosic, very orchestral, very all-encompassing style of repertoire. It’s all about the repertoire, and people want to be uplifted, so my job basically is to make sure that people really enjoy themselves.

– When did you start learning to improvise?

– I’ve been improvising from the very beginning – I started to play when I was three, but I didn’t start to read music until I was about 8-9. That presented its own problems, because by then I could play the basic [literature] but I had to go back and unlearn all that, and turn to learning the basics, like how to count, and to read music, all these things, it was quite something for me. But I’ve always improvised. I listen to a lot of music and have formulated my own style of improvisation.

– How will the audience grasp your particular art of sound choices within your registration?

– First of all, no two organs are the same. We have to remember that very organ is different. There’s a basic sort of design, of course, but every organ sounds different. The organist’s art is to select the sounds that work well for that instrument. That’s why we need a lot of time to practice because we need to get to know the instrument, to know what it can do, and what it can’t do. It’s very important to become at one with the instrument.

All the different sounds on all the keyboards are all organized in such a way that you can set them up with the various generals and pistons. You can select different sounds and store them: it’s important because this allows you to play the piece with ease. Over the years, of course, the art of registration, and all the facility for organ registration have become much more simplified. [Long ago] all these things were done by hand because there were very few registration aids to store the sounds you want. This is good because it makes you really learn to do all your own registration yourself without any assistants.

– Do you use assistants when you perform?

– Never. The one thing I can’t stand is having anybody assisting me. If you drive a car, you don’t have anybody helping you – someone managing the steering wheel or someone shifting the gears! I [need to be] in control of the whole instrument, which takes practice getting to know all of it. It’s wonderful to have a couple of days alone with it in the church, cathedral, or the hall, just to get to know the instrument.

– Do some organists have assistants do the pre-set?

– Yes. I personally hate it, but there are circumstances where one needs them if the organ has no registration aids at all, like those big French organs in Paris — St. Sulpice, for instance, where they have two assistants, one on either side. They pull the stops for me. It’s ok, but it’s another aspect you’ve got to [be concerned] about: will they get it right, will they forget something? You’re always at their mercy, basically. St. Sulpice’s organ is a massive instrument, with five manuals and lots of options, it’s a lot to think about. But it’s always been done that way.

– Tell us about the newer pieces on your program, especially the music of George Baker.

– George Baker is American from Texas but he’s known in Europe. His music is known amongst organists. He’s actually a dermatologist – that’s his day job. But he’s a very fine organist; he studied in Paris, so his compositions are very much in the French romantic style, which is why they appeal to me. The pieces of his that I’m playing are the amazing “Two Evocations” he wrote for another colleague, Nathan Lauber, a young American organist. I heard them on YouTube and I said to George that I wanted to learn these, so he sent me the score. I’ve recorded them, actually. The first one is a slow meditative piece, loosely based around two pieces by Louis Vierne; the second one is based upon an Easter plainsong hymn, and typically French.

– An organist I know said that sitting at a large organ console is like being in a cockpit of a plane, because you’re surrounded by buttons and switches. Can you relate to that feeling?

– Yes, I can. To the non-organist or non-musician, it looks like such a daunting thing, like, “how on earth…” It’s like walking into a cockpit of an aircraft with all these buttons all over the place. But for people who know what they’re doing, it’s pretty straightforward.

– Listeners often don’t realize just how big an organ is!

– For organ recitals in a concert hall, the large mobile console is what you see on the stage, but the pipes are behind the walls where the audience can’t see them. [For concerts with an orchestra and/or chorus, the smaller upstairs console is used.] When I’m playing downstage, you’ll see everything, and there’s a lot to see!

[The great organ of Müpa (click here to see how huge it is) has two consoles: both the upstairs version and the mobile console for the stage have five keyboards for the hands and one for the feet. Its 6,712 pipes of many sizes are behind the auditorium’s walls.]

– I’ve often wondered why marketing organ concerts is a bit more challenging that other types of concerts. I’m thinking one of the reasons could be need to disentangle potential audience members’ thinking of organs only in the context of the church. What are your thoughts?

– Yes, marketing organ concerts has always been difficult because the church is mainly where you’ll find them. But of course, more concert halls now have organs — many had them before, but a lot of newer halls are building instruments now. The concert hall organ’s sound is going to be very different from a church because in the [the latter] it’s that huge reverb which is part of what the organ is all about – the after-effect in the building… I think it’s a good thing that audiences are exposed to organ music in the concert hall, and of course you have to consider the repertoire for organ and orchestra, and works which feature the organ, whether it be operatic or choral. It actually might be nice to bring the religious aspect of the organ music into the concert hall, because, again, it’s diversifying the way the audience can hear something they were not really expecting, and be gently surprised enough to say “Oh, this is really very interesting – we didn’t actually know this was possible!” The thing is, there’s a lot of repertoire out there. A lot more concert halls are installing good organs now that can become part of their musical foundation.

– Have you been asked to consult with concert hall managements on the installation of an organ?

– Not in a consultant’s capacity, but I certainly would love to be presented with a blank check to commission a new organ in a new hall!

British organist Wayne Marshall performs on Müpa Budapest’s concert organ Tuesday, 8 February at 19:30.