Not long ago, I found a little pink rosebud sitting in a small sealed glass container in a Budapest antique store. I presumed it was designed to be hanging on a necklace. I thought, why should I wear something that was crudely extracted from its natural habitat, put into an airless prison, and probably decaying?

I began to realize this once-living rose was an oblique marker of time: time that we cannot measure, time that is unknown to the rosebud, its creator, or the wearer. On the darker side, perhaps it was a bittersweet memento mori. But objectively, it’s nothing more than a preserved floral specimen and a curious object that often prompts questions from those who see it hanging from my neck.

Artist Sándor Körei has a similar perspective. His intriguing sculptural essays about life – still life – are shown in a box rather than a painting. I first saw one of his works in a group show in MaMü Galeria on 29 April: placed on a pillar, his rendering of a bouquet in a glass box was so opaque that I wondered whether the flowers were alive but suffocating and/or creating their own perspiration. Or perhaps they were made of plastic.

Looking at it conjured up some of my memories. It reminded me closely of opera composer Richard Wagner’s song “Im Treibhaus” (In the greenhouse) wherein exotic flowers who had been transported out of their original environments were weeping with homesickness. The work by Körei had also inadvertently referenced my vivid memory of artist Mat Collishaw’s 2014 Istanbul exhibit “Venal Muse:” his sculptures in plexiglass boxes were the imagined results of flowers grown from genetically modified seeds. The results weren’t pretty.

Ani Molnár Gallery

But pretty is not Körei’s objective. His designs are sleek, mysterious, and deceptively simple. They make you raise an eyebrow and ask at least one question. His three latest works made their debut at Ani Molnár Galeria’s group show “Still in Bloom” on 22 June, where they join those of Péter Mátyási, Eszter Lázár, and Gideon Horváth. Each of the artists’ works riff on the theme of still life, using plants as inspiration, exploring them as symbols of beauty, fertility, ecology, love, loss, but mostly life and death.

Dead or alive?

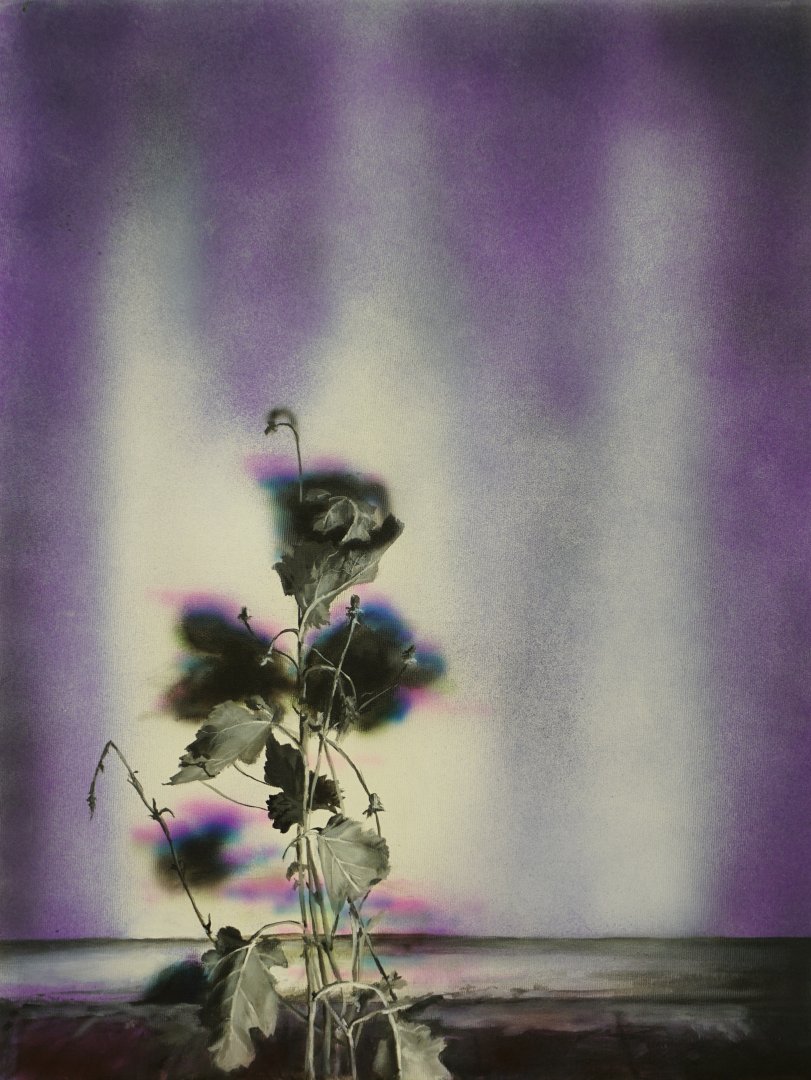

Horváth’s mustard-yellow bulbs made of beeswax (“Fruits of Our Loins”) hang in suspended animation from the ceiling, possibly suggesting extracted body parts or petrified plants memorialized in ceramic glaze, and depend on your state of mind to interpret. Lázár’s oversized closeup photos of orchids plunge our brains into glowing erotica, very much alive and ready to speak their secrets to us. Directly under them, one small sculpture (“Flutter”) atop a long skinny pedestal wrapped in shiny black garbage bags adds a clever touch of sub-rosa. Mátyási’s 3-D painting of dying flora (“Still Death”) plays with light waves within a prism that reflect on (in both senses of the word) decay and decomposition, and his image of a blackened birdcage turned upside down, like a spooky silhouette on the wall, flirts with ecological pessimism.

Körei’s dried field flowers (“Flowers in Vase 8”), erect like a giant spiky hairdo in their sunlit glass box, stand at attention — yet one or two seem to be ready to collapse. “Time is an active participant” he tells me after I ask whether the flower specimens inside the plexiglass are, in fact, in an airless compartment. “They’re not hermetically sealed, so the plants may be slowly rotting – another dimension that measures time.” My mind instantly conjures up sand sculptor Andrew Robertson, whose outdoor works are left to be destroyed by the elements. Once the work is finished, the process of decomposition, similar to planned obsolescence, is apparently not a matter of consequence or control.

Reflecting on the painterly tradition of still life, Körei’s original intention was to transfer that concept into a spatial work. In this regard, his stand-alone components serve as striking objects without any additional investigation. But conceptually, time as an element — one that’s not only constant, but is an unseen driver – is what Körei is chiefly exploring here. “The thing that’s important is not the flowers themselves, but it’s their process [of decay], as well as our response to it,” he explains.

artist and Ani Molnár Gallery

Does a built-in shelf-life present an issue for a buyer? Can the works be sold knowing that what is beautiful now may morph into compost? Will the cleaning lady mistakenly throw out the ‘dead’ flowers? “It depends on how the buyer reacts to the process. Some pieces, especially the ones with dried flowers, probably will not change that much,” he says. “But most often, we cannot predict.”

That’s precisely the intrigue. His boxes are our ephemeral windows into the inevitable. My little rose in glass will continue to mystify.

“Still in bloom” continues in Ani Molnár Gallery until 17 September 2022