In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the concept of „flow” which filtered into the world of music from sport, work and educational psychology. However, not all musicians like to talk about their best performances because of the fear of spoiling the artistry of their music making. So, with this article, I’d like to summarize what flow is and how it can help music making.

When we talk about flow, we may also come across the notions of „optimal” or „peak” performance. This is how Positive Psychology defines those experiences which, in a normal language, musicians simply would call a „great performance”.

Just like in other professions, in music performance „flow” refers to individuals’ subjective psychological state of mind, when they are completely immersed and fully concentrated in an activity (e.g. playing music), and this activity is very enjoyable and intrinsically rewarding. One great thing about flow actually is that doing something in the flow state is associated with peak performance (Cohen and Bodner, 2018). Why is that?

Flow plays a key role in motivation as experiencing flow is intrinsically rewarding, thus it encourages people to persist in and return to their loved activity. In turn, this experience fosters the growth of our skills over time (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009) which makes us capable of achieving peak performance. So, there are two key factors in the route towards peak performance: regularity and joy in the activity in the practice.

Flow generally has nine dimensions (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009). The first three are pre-conditions of flow:

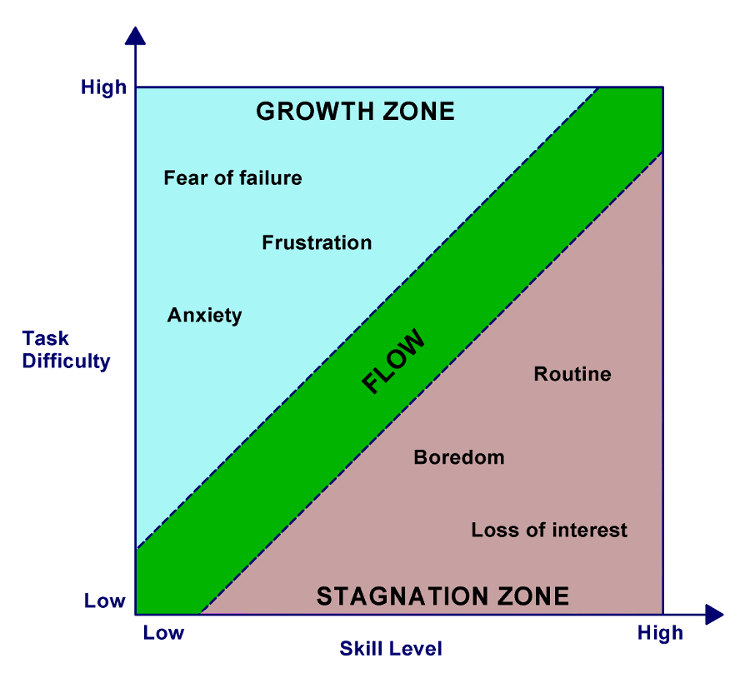

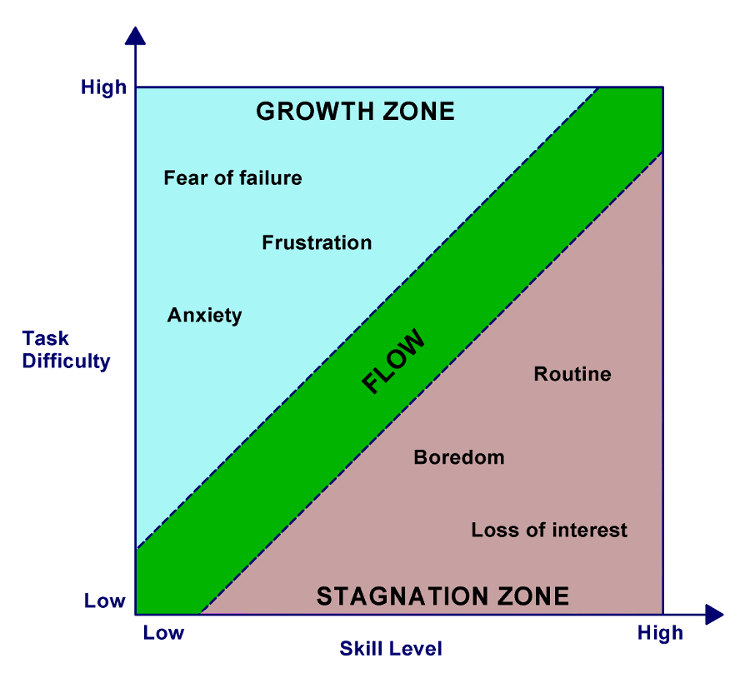

- Perceived challenge-skill balance (The task should not be too difficult to prevent feeling panicky but not too easy either, to avoid boredom)

- Clear goals (When you know where you’re going, you can focus your attention on taking meaningful action to reach your goal)

- Clear, unambiguous feedback (This helps you to adapt to any changing demands and adjust your performance to maintain the flow state. It occurs naturally when your skills are in balance with the task difficulty. I will discuss this a little later in this article.)

The remaining six dimensions are the ‘real’ experiential characteristics of flow:

- Total concentration (You are fully immersed in what you are doing, nothing disturbs you: not even your critical or praising thoughts)

- Autotelic experience (The experience in flow is intrinsically rewarding)

- Action and awareness merges (The activity you are doing becomes spontaneous, almost automatic; there is a feeling that the task and you are united)

- Sense of control (Being in control)

- Loss of self-consciousness (In a flow state, you are too involved in the activity to care about protecting your ego, you just are immersed in the activity which you enjoy doing)

- A distorted sense of time (The experience that time transforms)

Reading all this, you may ask whether flow makes musicians more satisfied?

In a recent survey (see Habe et al., 2019) researchers explored elite musicians’ and top athletes’ flow experiences and the extent they felt satisfied with their lives. They found that the nine flow dimensions (that I have described above) somewhat were related to life satisfaction, but only the

challenge-skill balance (1.) was a significant predictor for satisfaction with life.

This means that choosing an appropriate piece or technical exercise is the most critical part of your practice if you would like to feel contended on the long run. This is especially crucial if you are a perfectionist, since perfectionists are easily dissatisfied with their results.

In the same study, the level and occurrence of the nine dimensions of flow between the two groups (elite musicians and top athletes) were also compared. Interestingly, musicians and athletes differed from each other in four points:

Musicians’ scored higher on autotelic experience (5.) and distorted sense of time (9.), while in the athletes group the clear goals (2.) and unambiguous feedback (3.) were higher. If you check the nine dimension of flow, you can see that athletes are better creating a supportive mental state with the preconditions of flow.

But what musicians can learn from this difference? Definitely it is worth setting more specific and clear goals. I will make a separate blog post about goal setting but until then you can listen to the podcast episode here I recorded earlier with Dr. Bridget Rennie Salonen in which she lists some key points relevant to goal achievement.

The same study (Habe et al., 2019) also showed that musicians are more likely to experience flow in group than in individual performance settings. This makes sense, doesn’t it? But surprisingly, males experienced flow more often than females in both groups (elite musicians and top athletes).

What’s the matter with comparing professional and student musicians’ flow experiences?

Well, researchers found that this balance seems to be better among professional musicians (Kirchner et al., 2008) as professional musicians’ performing skills and the frequency of their flow experiences were higher than of student musicians.

In this sense, does this mean that it is nearly impossible to get into the flow state for beginners or less experienced musicians? No!

Again, the key to success is always choosing the right challenge and difficulty level in your music repertoire. People like to push themselves too hard to advance their skills as quick as possible but in order to reach flow (which in turn deepens our newly acquired skills!), we need to carefully choose what and how we want to practice. We know that the balance is appropriate when we feel great in what we are doing, that it feels neither boring nor frustrating. In other words, it is fun!

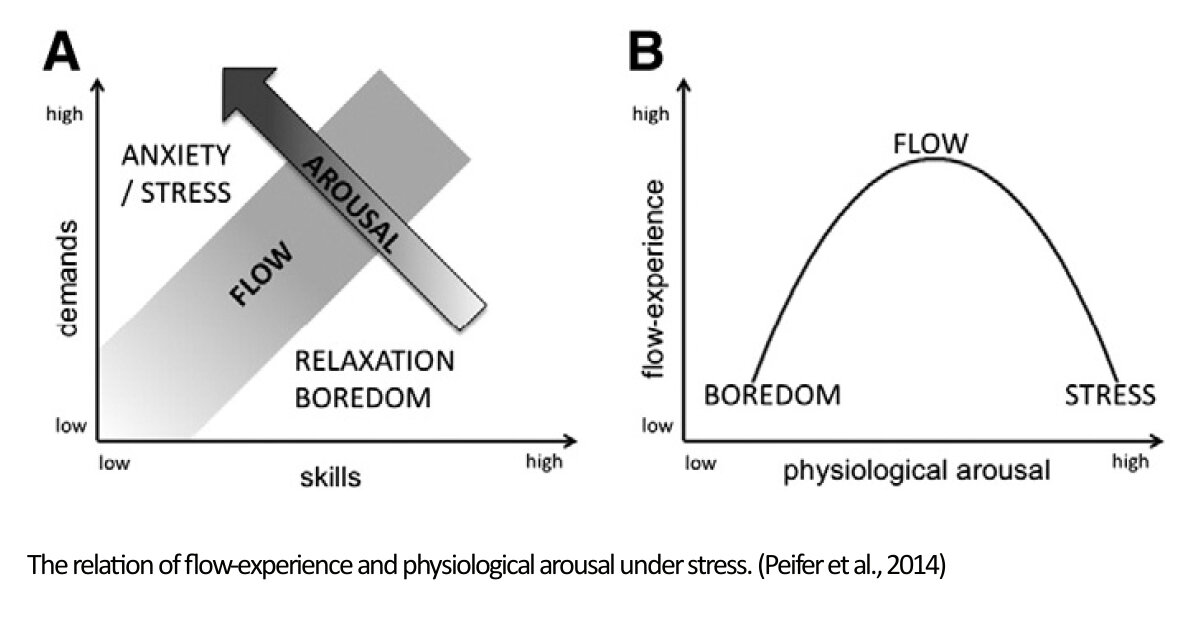

The scientific explanation for this is that the psychophysiological basis of flow works as an inverse-U relationship between people’s physiological arousal and flow (Peifer et al., 2014).

If you look at the figure about psychological arousal (Peifer, 2014), you can see that, for instance if you are too bored, you cannot enter the flow state because your arousal level is not high enough. Conversely, if you are anxious or stressed for whatever reason, it means you are in an over-aroused state and again the chances to get into the flow-state are quite low.

Does flow reduce stage-fright?

Not directly but it helps. Practically, it seems that performance anxiety and being in the flow state can exist simultaneously. The good news, however, is that flow proneness (the ability to get into flow) is associated with lower levels of performance anxiety. This also makes sense. Remember that I mentioned earlier that in flow state musicians experience less amount of disturbing thoughts. So no wonder, they sense stage fright less frequently as well as less intensely (at least this is what Kirchner et al., 2008 found among undergraduate music students).

On the other hand, the high flow – low stage fright tendency works among professionals as well (Cohen & Bodner, 2018). The majority (85.5%) of professional classical orchestral musicians experience flow quite often and only about half of them experience stage-fright sometimes, often or almost always. Well, this ratio could be better, do you think?

Certainly, there is so much to do in order to support musicians’ and music students’ practice, and flow is only one of them. At least we know that flow and stage-fright are antithetical states in which the presence of one minimizes the magnitude of the other, which is great news!

What musicians actually need is to get access to fostering techniques that facilitate flow to improve their practice in every sense!

Hereby, I make a promise to you to create another blog post in the near future in which I will summarize the flow supporting techniques.

Until then I wish you well to remember: „Done is better than perfect” 😉

References

Cohen, S., & Bodner, E. (2019). The relationship between flow and music performance anxiety amongst professional classical orchestral musicians. Psychology of Music, 47(3), 420-435.

Habe, K., Biasutti, M., & Kajtna, T. (2019). Flow and satisfaction with life in elite musicians and top athletes. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 698. https://www.frontiersin.org/

articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019. 00698/full

Kirchner, J. M., Bloom, A. J., & Skutnick-Henley, P. (2008). The relationship between performance anxiety and flow. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 23, 59–65.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 195–206). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Peifer, C., Schulz, A., Schächinger, H., Baumann, N., & Antoni, C. H. (2014). The relation of flow-experience and physiological arousal under stress—can u shape it?. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 62-69.

The original article is available at the Perfactionist website.