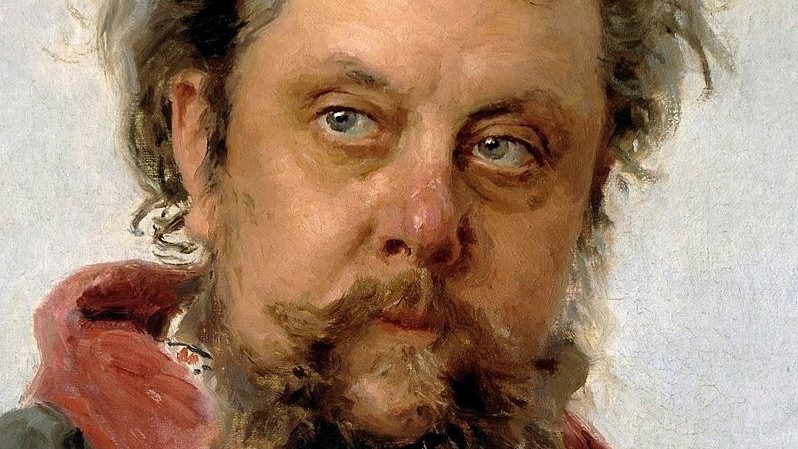

What is Mussorgsky’s music piece „Pictures at an Exhibition” about? About the pictures at an exhibition, the obvious answer would be. In my view, however, there is a lot more than that involved. The primary frame of interpretation, of course, is the topic given in the title of the composition. This programme music is, in fact, a musical reflexion on a real exhibition, and Mussorgsky even supplied the titles of the pictures, as well as their subject matters.

However, the audience knows little about the artist who made these pictures: about Victor Hartmann, a good friend of Mussorgsky – painter, stage-designer and architect (1), and this friendship provides the key to broaden the frame of the composition’s interpretation.

Mussorgsky was profoundly fond of Hartmann, so it was a painful shock for him when the painter suddenly died in 1873. As he wrote in a letter: „I don’t know if Hartman finished the construction work. This senseless death keeps taking its toll, irrespective of the fact whether we need its damned visits.” (Mussorgsky M.P. 1970: 106)

He does not only blame death, but himself as well: „I remember when Vitja travelled to Saint Petersburg the last time, we accompanied him… just opposite St. Anne’ Church, Vitja leaned against the wall and got pale… I asked him (calmly): What’s the matter? – I am short of breath, he said… As I was also familiar with artists’ nervousness and heart problems myself… (with the same calmness) I told Vitja again: Just have a little rest, dear friend, and then let’s go on. Well, we were talking in this light manner about something that, in the end, robbed us forever of the person we loved… How foolish we are! If this conversation comes into my mind now, my heart sinks at the thought that I felt uneasy then for being worried… and I failed to help this man, such a man… how shameful!” (Mussorgsky M.P. 1970:107)

Mussorgsky’s self-reproach was intense because he considered Hartmann an exceptionally gifted artist and, when he died, he did not only lose a friend, but his death also broke the career of a promising artist who had been destined to lay the foundation of modern architecture which also integrated the Russian traditions into itself. „I remember our last conversation (how could I forget it!)… he entertained me with his idea of a Russian-style architecture. This stlye, although adapted to the demands of our time, is still Russian style or, as he liked to phrase it: a „sophisticated” Russian style… If we recall the precious memory about the houses built a-la Makarov, the chapel of the Summer Garden, the flight of stairs that „bowed to the ground” at the Vienna World Trade Exhibition – and it did bow to the ground, actually, in front of the whole world (the Russian slave woman did not deny her true self there, either) -, and then we add to it the bare frame of the folk theatre in Moscow (not to mention its sophisticated details and its independence but simply its bare frame), one’s heart sinks at the thought how much Hartman could have contributed to art, had he not died so early!” (Mussorgsky M.P. 1970:105)

Mussorgsky cannot find consolation for himself after Hartmann’s death: „The wise console us foolish people by saying that although he is no longer with us, his works of art still live and will continue to live… but how many artists are granted the blessed fate of not being forgotten? This kind of reasoning (together with the horse-raddish-stimulated tears) is only the product of man’s self-love. To hell with your wisdom! If his life was not futile but that of a creative man, it is disgraceful to take pleasure in finding consolation and relief accepting that his creative work has ended. No, there cannot be peace or consolation – this would be immoral. (Mussorgsky M.P. 1970:108)

A year passes and, in 1874, an exhibition is organised from Hartmann’s paintings (Frid: 1966). Mussorgsky is still troubled with doubts: Hartmann will be forgotten, because what has been left behind after his death? Watercolours, some stage designs, building designs and building models. It is then that he starts composing „Pictures at an Exhibition”.

It is interesting that at the first sight there seems to be no connecting idea between the pictures portrayed in the composition. Let us see: the composer first takes the picture of the gnome, then the old castle, then comes the picture of children quarrelling in the Tuileries Gardens, then the musical portray of the hay-cart (bydlo), followed by the ballet of unhatched chicks, then the arguing Jews, the market place in Limoges, the catacombs, the hut of Baba Yaga standing on fowl’s legs and, finally, the great gate of Kiev.

It is highly unlikely that, following such a serious emotional crisis, the paintings were selected and arranged in the composition randomly! Had Mussorgsky been an impressionist composer, this theory might perhaps have ground, saying that he tried to depict the atmosphere of the exhibition in music. Therefore, if we dismiss the hypothesis that Mussorgsky selected the ten paintings randomly for his composition, out of a collection of several hundred works of art, we must find the underlying principle behind his choice of the particular order in which the pictures follow one another in the composition…

We should start from the assumption that the musical representation of the given pictures evokes memories and feelings related to the lost friend, since the mere sight of the chosen paintings is unlikely to induce such deep emotions. This assumption is supported by the fact that if it was merely about the pictures at an exhibition, the musical composition should follow the pattern of promenade (walk) – picture – walk, because in that case the walk would lead us from one picture to the next one. However, this is not the case: the promenade sometimes is omitted, and the pictures come one after the other. At another point the promenade motive is integrated into the music describing the given painting (Pándi 1980). Last but not least, Mussorgsky himself talked about his inner struggle at the time he was composing the music: „My mind is kept busy with Hartman, just like it used to be with Boris – sounds and thoughts whirl in me, and I am ruminating and brooding over them, and can hardly put anything on paper…” (Mussorgsky, M.P. 1970: 126)

And it is probably not by chance that he gives his composition the sub-title: In Memory of Victor Hartman. (Mussorgsky M. 1997: 600)

The topic of death has inspired several composers – we should only think of the Dance Marcabre by Liszt and Saint Saens, or Schubert’s Death and the Maiden. Actually, Mussorgsky also deals with this topic in some of his other compositions: for example, in Songs and Dances of Death, or in his operas (Boris Godunov, Hovanscina). It is a common element in the above pieces that the portrayal of death was inspired by some work of literature or fine arts, or by some musical motif.

„Pictures at an Exhibition” differs from the above ones in that it was composed on the basis of the artist’s own experience, which is the reason why it reflects the process of grieving so perferctly. Mussorgsky gives such a faithful description of the emotional process he was going through that it can be interpreted by means of the theory of grief used in psychology.

Telling the plain truth is, in fact, the most important principle for him: „…in the way as Mussorgsky does it sometimes, in leitmotive-like exclamations which, at the same time, summarize his musical-aesthetic credo very simply: „I want the thruth!”… Mussorgsky’s music is not attractive to the „normal” ears of his time, but it is profoundly true, to the point of embarrassement. Its compelling power challenges the conventional standards of playing music in the „beautiful” way which was believed to fall in line with the western style,… But what does this truth mean for Mussorgsky? First of all, the reality or truthfulness of the portrayed characters and situations, that is, the re-exploration of their authenticity. How do human beings behave in their own world, what is one’s world like? How does the individual speak and behave in interactions and in situations? Reclaiming the truth means, first of all, dialogues integrated in the situations (in his letters, he often discusses the concept of the dialogue-opera), in which the voice, tone, motif, melody pattern and the collision of the musical characters create the situation for the truth of the music and word.” (Balassa 1998)

As it will be seen in the following, this focus on dialogues has great importance in „Pictures at an Exhibition” as well. The anatomy of grief is described by several pscychological models sharing basically similar considerations. Essentially, they all distinguish various stages of grief. It is important to stress that „the reaction given to loss is determined by a number of factors: the nature of relationship with the deceased, the way the person died, the age of the bereaved, their sex, personality, previous life events (depression, in particular), their actual mental condition. As a result, grief is always different with each individual.” (Pilling 2003: 28)

Thus, it is not reasonable to stick firmly to the phases of grief because, despite their similarities, the psychological models describing the process also differ from one another: for example, in the number of the phases and their interpretations. What is more, „the complex process of grief cannot be easily divided into clearly distinctive stages.” (Pilling 2003: 28) However, these phases are still useful as they can serve as a guideline in interpreting the composition.

Keeping the above in mind, at first I thought of the simplest model of three phases to be chosen for the analysis of the composition. Then I considered the option of the four-phased model (Kats, 1995), mainly because it describes the mental process of grieving through the dreams of the bereaved. This model seemed to be more suitable for the analysis of a musical piece composed in an agitated mental state, and that was one of the main reasons why I finally decided on using it. (The difference between the two models is that the four-phased model divides the second phase of the three-phased model into two parts. Consequently (in my view, at least), there is no basic contradiction between the two models – only the interpretation of the second phase is more differentiated with Kats.)

The division of the Kats-model is the following: the first phase is described as consternation, shock and denial; the second one as a period of overwhelming emotions and suffering; the next phase is characterised by searching, finding and letting go and, finally, the last phase establishes a new relationship with ourselves and with the external world, which is also called the re-organization of our lives.

And now, let us take a closer look at the mental process of grief as reflected in music.

First we should say a few words about the promenade (or walk). The promenade is the composer’s self-reflection on the emotions induced by the musical picture he has composed: „… the connecting parts /on the theme of the promenade/ are beautiful… my own physiognomy can be seen in the connecting parts.” (Mussorgsky M.P. 1970).

In other words, Hartmann’s pictures constitute the starting point, on which base Mussorgsky composes the musical pictures, and arranges them in accordance with the mental process of grieving. Moreover, by inserting the promenades, he interprets his own mental process and, in fact, this dialogue leads him to the solution of the problems he is experiencing during grievig.

We should not forget about another aspect of the composition: namely, it was not by chance that Mussorgsky wrote the instruction „in Russian style” to the promenade (first walk) in the score. (Mussorgsky, M. 1997: 600) The controversial relationship between the western and Russian cultures can also be observed in the composition, as a true mark of the aesthetic views he shared with Hartmann: „he entertained me with his idea of a Russian-style architecture. This stlye, although adapted to the demands of our time, is still a Russian style or, as he liked to phrase it: a „sophisticated” Russian style…” The fundamental role of this „sophisticated Russian style” will appear in the last phase of grief.

Let us have now a closer look at the musical pictures.

The first picture is the gnome, which causes consternation – this is, in fact, the first phase in the process of grieving. The effect of shock induced by the picture can be felt in the promenade that follows.

The next two pictures still belong to the first phase, and the common feature in them – by using the terminology of Kats – is impassivity, however, „.. this impassivity is far from being the result of dried out emotions: on the contrary, it is caused by an emotional shock. The bereaved is numbed by the very intensity of emotions: it is the accompanying phenomenon of the denial to accept the loss.”

The troubadour melody of the old castle (Pándi 1980) reveals that Mussorgski truly loved his lost friend, Hartmann, but „… he conjures up Italy under the Russian sky. This sky is projected over the Italian castle, by the melodiousness of the highest part coloured by eastern motifs. This obvious and intentional mixing of intonations creates a distance from the passionate emotions of the troubadour,…” (Pándi 1980: 274), resulting in a feeling of stupor. These pictures are again followed by a walk – that is, by self-reflexion.

The last picture of the first phase is of children quarelling after play in the Tuilleries Gardens. (Mussorgsky, M. 1997: 600), expressing the composer’s anger in a toned-down form – as it is about creating a musical picture of bickering kids – and, by doing so, it expresses denial about the loss.

„It is hard to admit that we are helpless when death is concerned. When we rage, when, in many cases, we make extremely great efforts to find the guilty party, we delude ourselves that we are not hopeless.” (Kats 1995: 68)

Thus, accepting the anger which manifests itself in the musical picture is problematic, due to the feeling of helplessness: „No, and no, again, there cannot be peace or consolation.” Therefore, there is no promenade after this part, but it is immediately followed by an outburst of immense pain so far suppressed – this is the second phase of grief -, with the musical picture of the hay-cart (bydlo). Mussorgsky is sobbing desperately. The hay-cart is followed by promenade – it can be so because the feeling of pain and crying are already acceptable emotions for the bereaved.

The new shock induced by the hay-cart is followed by a bizarre musical picture full of anxiety: the dance of the unhatched chicks. (Mussorgsky, M. 1997: 600) It must be noted that Mussorgsky gave a completely new interpretation to Hartmann’s picture. The original picture was, in fact, a drawing used for stage scenery, in which a man in an egg-shell costume can be seen. Here, the composer’s self-reproach is surfacing: ”…one’s heart sinks at the thought how much Hartman could have contributed to art, had he not died so early! … and I failed to help this man, such a man!” That is why he gives the title ’dance of the unhatched chicks’ to the piece: it is a kind of dance macabre, of those who will not fulfil their destiny because they die much too early – already in the egg-shell. This, again, is not followed by a promenade, because, similarly to the picture of children quarreling in the Tuilleries Gardens, it reflects an unsettled state of mind.

The next musical picture is interesting from an additional aspect: it was composed by using two of Hartmann’s pictures: it is the dialogue of the two Jews: the rich and the poor one. It is an angry and helpless accusation, the non-acceptance and denial of sudden death: „this senseless death keeps taking its toll, irrespective of the fact whether we need its damned visits.”. However, there is no escape – in the end it must be accepted: death is irreversible. This musical picture is followed by the first promenade – signifying the fact that there is a marked dividing line here – Hartmann’s death has been acknowledged!

The next phase of grieving is searching, finding and letting go: „this makes the inner dialogues possible.” (Kats 1995: 75)

Mussorgsky is looking for Hartmann in the bustle of the market place at Limouges, which is interrupted by the grim picture of the catacombs. There is no promenade between the two pictures, because this time the two pictures jointly describe a process: Hartmann appears in the painting, among the heaps of human skeletons! This is one of the most significant steps in the process of accepting death. „Con mortis in lingua mortua.”, Mussorgsky writes in pencil on the margin: with the dead, in the language of the dead (Muszorgszky 1997: 600), and that is the point where, in the language of music, acceptance becomes complete.

Still, there is another emotional burden for Mussorgsky: Hartmann will be forgotten, and he is responsible for this because, due to his sudden death, Hartmann’s architectural work remained in the form of designs only. Mussorgsky maintains a dialogue with the ghost of Hartmann: „the enigmatic music of the scene is actually the rerurn of the familiar melody of the Promenade, under eerie, prolongued octave-tremolos.” (Pándi 1980: 275)

„The creative spirit of the dead Hartman is leading, calling us to the skulls, and the skulls are slowly shining up.” (Mussorgsky 1997: 600), Mussorgsky writes on the score, which recalls Hamlet’s meeting with the ghost: „Rest, rest, perturbed spirit…” „The time is out of joint: – O curséd spite, That ever I was born to put it right!”

The musical picture of The Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba Yaga), (Mussorgsky 1997: 600) is the point where starts the magic, in which Mussorgsky builds up the Great Gate of Kiev as a masterpiece of the new Russian architecture, not from stones, however, but from musical notes. And this has taken us to the last phase of grief, in which we create a new relationship with ourselves and with the external world. „Its precondition is that the deceased must be transformed into an „inner figure… everything that earlier existed in the relationship itself, now enriches the scope of the bereaved’s own potentials.” (Kats 1995: 77)

The bells of the Great Gate of Kiev bid a final farewell to the deceased who, by now, has become immortal through the musical portrayal of his pictures – and thus Mussorgsky could also free himslef from his tormenting self-reproach.

References:

- Balassa, P.: Modeszt Muszorgszkij szenvedése és nagysága / Levelek, dokumentumok, emlékezések. In.: Muzsika, 1898, április 41. évfolyam, 4 szám.

- Frid, E.: Mogyeszt Petrovics Muszorgszkij. 1966. Budapest, Zeneműkiadó Vállalat. 114. oldal.

- Kats. V.: A gyász egy lelki folyamat stádiumai és esélyei. Stuttgart 1991.

- Muszorgszkij, M.P.: Válogatott levelei, 1970, Zenemű Kiadó. 126. oldal

- Muszorgszkij, M.: Levelek, dokumentumok, emlékezések – Összeállította és fordította Bojti János és Papp Márta, Budapest, Kávé Kiadó, 1997.

- Pándi, M.: Hangverseny kalauz IV. Zongora művek. 1980. Zenemű Kiadó Budapest. 272-275. oldal

- Pilling, J.: Gyász. 2003. Medicina. Budapest. 27-36. oldal

* I wrote Hartmann’s name with double ’n’ in this study, however, it is spellt by one ’n’ in the volume of Mussorgsky’s selected letters published in 1970. For authenticity, I kept that spelling in the quoted parts.