On the anniversary of Ferenc Liszt’s birth, 22 October, the composer’s unfinished opera Sardanapalo will be performed as part of the Liszt Festival, and we interviewed Cambridge University music historian David Trippett, who not only found but also orchestrated the unique piece thought to be lost.

– How did you get close to Liszt’s music?

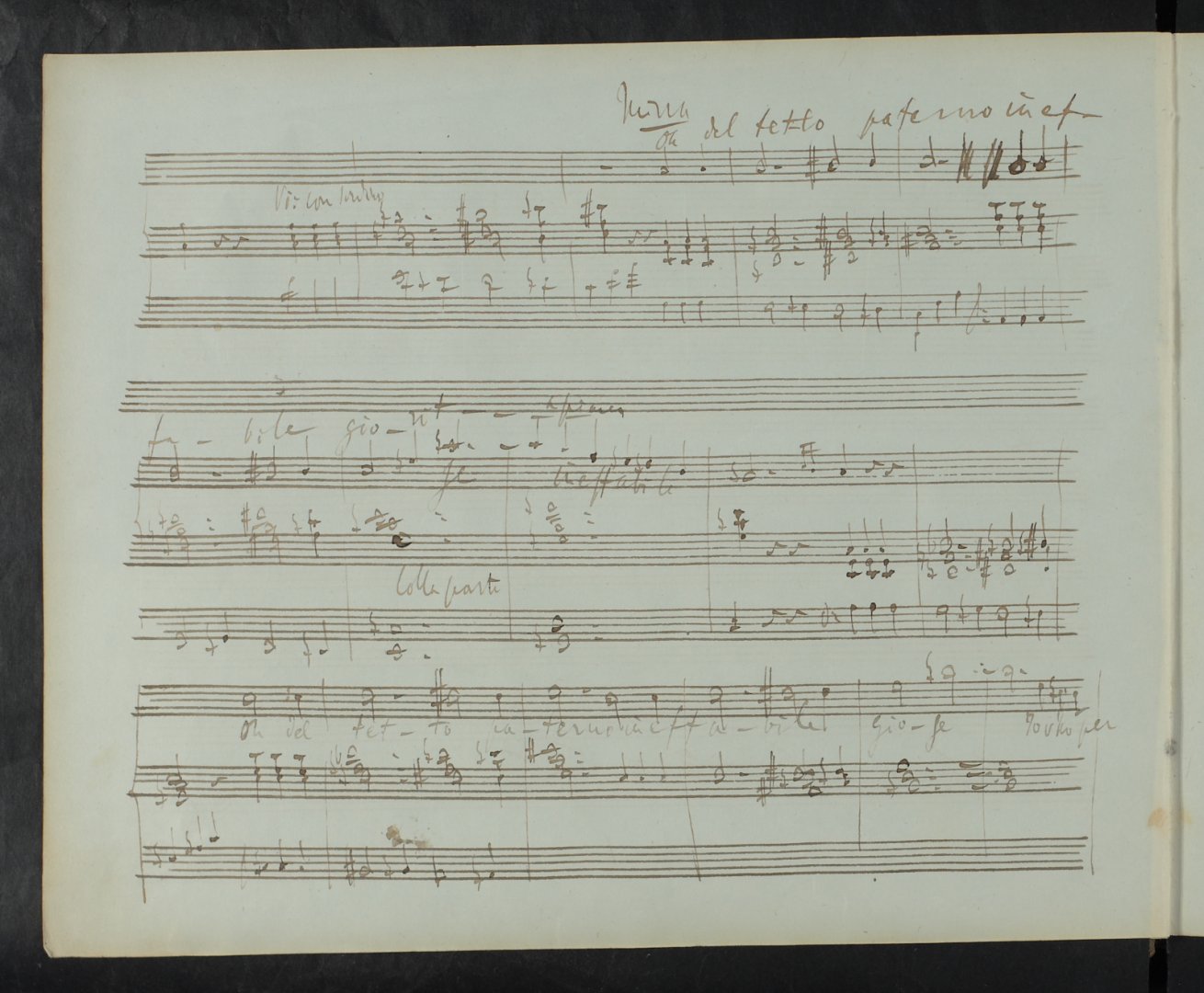

– After my first degree in musicology at Cambridge, I studied in Leipzig. At that time I worked with many singers as a piano accompanist. I knew that the Weimar archive was a musical goldmine for Liszt’s sources and I thought I might be able to surprise my musical partners. I was aware of the small N4 music book, which supposedly contained fragmentary sketches for an opera. I opened it in the middle, and was immediately struck: there was a beautiful soprano or tenor aria almost fully written out. I could hear it clearly in my head, and it was extraordinary that this hadn’t been heard.

The manuscript made quite a special impression on me, because I could see that what was written there was certainly not just an atomized stream of little thoughts, a fragment of an idea, but a very well thought-out piece of music, with a lot of hours of work put into it. The vocal parts were complete, their lyrical lines gold-plated, from which the entire first act of an opera, Sardanapalo, emerged.

– When did you decide to reconstruct the play?

– I have to admit that I had to put it aside at that moment to finish my doctoral studies at Harvard, but I knew I had found something I still needed to work on, so I came back to it later. As I mentioned, the music was not fragmentary in the sense that, say, Beethoven’s 10th Symphony is fragmentary, so it wasn’t a question of completing a piece or putting together short, isolated themes and fragments of music, but of whether this continuous excerpt was worth orchestrating. I must add that it was clear from the manuscript that Liszt was thinking in terms of an orchestra, since he also wrote here and there which instrument he intended to use for which part. For me, the real question was really whether, as a researcher and scholar, I had the task and the authority to orchestrate the piece, or whether my work had to end with a critical edition, i.e. in making what I had found available to scholars in libraries. In the end, I set about orchestrating it because I felt a moral obligation to make audible all the dimensions of what Liszt had inscribed in the N4 manuscript.

– Liszt was a celebrated pianist of his time. Why did he want to write an opera?

– Liszt had few serious competitors as a pianist. He was celebrated in Paris, Vienna, London, Pest and even St Petersburg, but he felt insufficiently recognised as a composer. Even Robert Schumann once severely and publicly criticised his skills as a composer. Liszt must have been hurt by this. His letters show that he saw completing an opera as the key to being accepted as a composer. He was certainly influenced by his friend and fellow composer Richard Wagner at the time, but Liszt regarded Rossini’s oeuvre as a closer example, music he saw as the pinnacle of innovation in Italian opera. Needless to say, Liszt had similar plans for Sardanapalo, based on Lord Byron’s poem.

– What is the reason why the opera was not finished?

– Clearly, the lack of a libretto. Liszt commissioned a French writer, Jean Pierre Félicien Mallefille, to write the libretto and thought that he would later have the text translated into Italian. The venture was unsuccessful for several reasons. On the one hand, Mallefille did not consider the request ambitious enough and wasted almost a year, and on the other, Liszt did not know enough Italian to supervise the correctness of the translation from French. Liszt finally asked his close friend, Princess Cristina Belgiojoso, to help him with the libretto, and she asked a mysterious Italian poet (living under house arrest in Paris) to write it. The first act was completed, which Liszt accepted without alteration and set to music, but he was not satisfied with the second and third acts. He requested changes, but never received them. The voices of Italian independence were resurgent, Liszt lost his contacts, and the poet, whose identity was never known to Liszt, could not be contacted directly.

– The first act was first performed in Weimar in 2018. Has the score changed at all since then?

– There have been minor improvements, of course, including some corrections, as I’ve continued to work closely from the manuscript all along. They are minor but audible, but I think that the score is now really complete and I am very happy that it will be performed in Budapest in the wonderful concert hall of Müpa Budapest.

– What will the Hungarian audience hear? Will we recognise Liszt?

– From the very first moment. I am sure of it. I must stress here once again that the orchestration does not mean that I have changed anything in the music. In the course of the work, I studied closely the works written in the Weimar period, the early symphonic poems and Liszt’s repertoire of transcriptions and paraphrases of Franco-Italian operas. The conductor for the evening will be Kirill Karabits, to whom I showed the work before its premiere in Weimar in 2018. He too was immediately struck by how much of the piece echoes everything that we attribute to Liszt – harmony, voice-leading, themes, lyricism. I can’t say that I’m not thrilled that the work will be performed in Budapest, since no one knows more about Liszt than Hungarian audiences. With an open mind, I’m sure it will win the hearts of everyone.

– The piece is performed by Staatskapelle Weimar.

– Yes, it is a remarkable bringing together of cultural centres that this work is being performed in Budapest by the Staatskapelle Weimar, which Liszt himself conducted for about a decade, and on 22 October, the anniversary of Liszt’s birth.

– Five years have passed since the premiere in Weimar. Are you continuing your research on the opera of Sardanapalo?

– Reflecting on the musical life of the 19th century and Liszt’s art in it, I have two books in preparation. As far as the opera is concerned, several questions remain unanswered, but it is difficult to make progress without new sources. One thing is certain, the libretto for the second and third acts of Sardanapalo has been completed, but we have no idea as yet of its whereabouts.